Feature Story Regional Analysis And Implications Of Major Industries In China(Shipbu…

페이지 정보

작성자 최고관리자 댓글 0건 조회 4,616회 작성일 19-10-30 14:56본문

Chul Cho et al., Korea Institute of Economics and Trade Chul Cho et al., Korea Institute of Economics and Trade

1. China’s Shipbuilding Industry Trend

(1) Production Trend

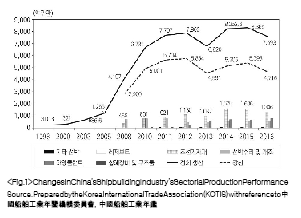

Around 2000, many of China’s major industries were growing rapidly. At the same time, the shipbuilding and marine industry also experienced rapid growth, exceeding 30% annual growth. In 2000, China accounted for around 5.7% of the global shipbuilding and marine market, based on CGT. As the global market boomed, heavy investments into construction capacity helped raise China to the world’s second-largest market shareholder by 2009, and eventually number one on most indicators by 2010.

Despite a sharp decline in global demand following the Global Financial Crisis(GFC) in 2008, the Chinese government actively created demand and provided financial support to help China rank first in both order volume and order backlog by 2009. And in 2012, China was ranked first on indicators for order obtention, construction, and order backlog. The completion of three major shipyards, all of which were a part of projects promoted by the government, construction capacity expand greatly, especially among State-owned Enterprises(SOE). However, following the GFC, the global market entered into a recession, leading to the closure of many private and local government shipyards.

The Chinese shipbuilding industry’s sectoral production, unlike Korea, steadily increased by focusing on larger ships, ship repairs, remodelling, and leisure boat production. In particular, prior to 2010, ship repair and renovation accounted for the highest share after steel ship construction. In the following years, the shipbuilding equipment sector’s market share decreased but was able to secure global competitiveness. The offshore plant sector, which was focused on jack-drilling vessels since 2011, surpassed Singapore, as the dominant player in 2012. But, like Korea, jack-drilling vessels were a cause for considerable losses around 2015. Operating losses in China’s offshore plant sector amounted to 1.5 billion Yuan in 2015 and about 5.99 billion Yuan in 2016. Most of these losses were from SOEs which concentrated on offshore plants backed by government-led promotion and policy support.

In relation to Korea, China’s major export items to Korea were bulk carriers and hull blocks, with tankers accounting for a certain proportion. Ship fund bulk carrier exports increased sharply until 2010 but have since declined rapidly, as has hull blocks too.

(2) Domestic Demand Trends

China’s shipbuilding and marine companies, which had several newly expanded facilities, were expected to be hit following the onset of the GFC. However, the impact was alleviated as demand was created by strong policy support from the Chinese government. Despite efforts, the prolonged global market slowdown led China to undergo serious restructuring.

The strong capital mobilization capacity of ships in China’s financial sector was already a major source for the global ship finance industry. Furthermore, the demand for ships linked to China’s overseas large-scale resource developments was also well connected to Chinese shipbuilders. Immediately following the GFC, ship finance syndicated loans dropped sharply to USD$33 billion, about 40% of the previous year, but did temporarily showed signs of recovery. However, due to long-term market stagnation, loans decreased due to the sector’s fiscal deterioration.

China’s ship-related financial resources were more direct than syndicated loans, making it difficult to compare directly. But, Marine Money estimates that financing executed by major Chinese banks expanded to around 20% of the world’s ship-related financing. In particular, shipbuilding funds and lease financing, which were active since 2010, as well as low-cost loans and domestic construction conditions, were creating demand for the shipbuilding and marine industry.

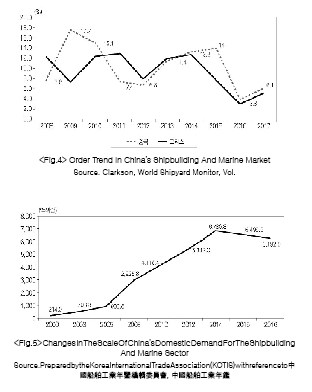

The Chinese government’s capacity was influential enough to compensate for shrinking global demand in the shipbuilding and marine market. Consequentially, China overtook Greece to emerge as the world’s largest client country in the merchant ship sector following the GFC. Total new ship orders in China amounted to approximately $89.8 billion from 2009 – 2017, including demand for new ships and ships from the state-led policy to retire old ships in order to make fleets efficient. Within this period, China surpassed Greece as the world’s leading investor in ships. However, China’s demand supplied was limited under the ‘guolun guozao’ policy, – China’s distribution will be cared for by China – domestic companies targeted for foreign investment are subjected to high taxes; instead, investment was re-routed to core manufacturing equipment R&D and investment was limited overall.

China’s domestic shipbuilding and marine market was worth 21.4 billion Yuan in 2000. Beginning in 2005, the market grew rapidly until it reached its peak in 2014 when it began to decline. China, like Korea, had difficulties from the economic downturn in the commercial ship sector following the GFC. However, the downturn was short-lived and the market revived from 2011 to 2014 following national efforts to create demand and also support the offshore plant jack-up market. However, domestic demand began to decline again from prolonged market stagnation. The equipment sector, a sub-sector within China’s shipbuilding and marine market, also followed suit rapidly growing from 2008 to 2014.

(3) Competition Structure And Characteristics Of The Shipbuilding Industry

1) Competition Between Imports And China’s Domestic Production

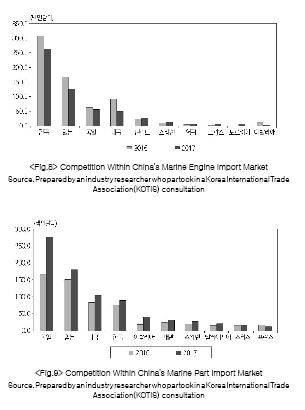

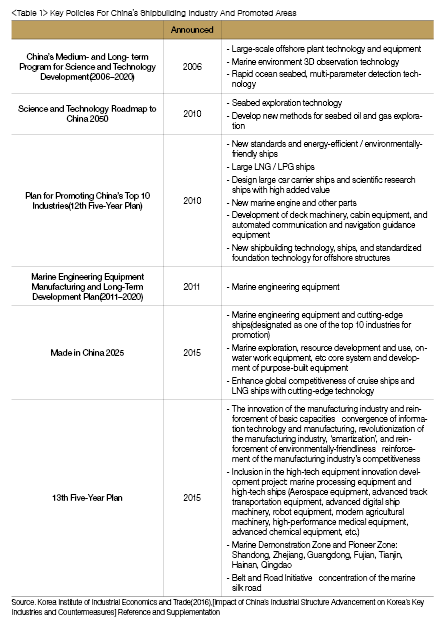

In the case of ships or offshore plants, there were very few instances where imported and domestically produced products compete for domestic demand given China’s domestic construction and localization policies. Since demand for ships and offshore plants came mostly from state-owned shipping companies and state-owned energy companies, almost all ship types could be produced within China. In particular, ship and offshore plant demand increased from domestic shipbuilding and marine companies due to the Chinese government’s ‘guohuo guoyun’ – Chinese made goods will be Chinese transported – and ‘guolun guozao’ policies. Even if domestically built ships and offshore plants were of lower quality or lower efficiency, companies continued to build domestically and gradually improved quality and efficiency. Unlike finished goods such as ships, manufacturing equipment often used by non-SOEs were generally built overseas. At times, state-owned shipyards used overseas equipment to meet the requirements of overseas ship owners. However, if domestic equipment was available, then companies tend to use domestic equipment as advocated by state policies. Private companies, on the other hand, unless specified by the ship’s owner, preferred to install equipment with better quality than price. In other words, competition between imported and Chinese-manufactured finished goods rarely arose in China’s domestic market. However, when it came to equipment, competition between imported and domestic goods tended to arise more often. For example, Korean and other non-Chinese marine engines were generally preferred to Chinese engines, but this rapidly declined from joint marine engine production with European and Japanese companies in China.

2) Competition Amongst Countries In The Import Market

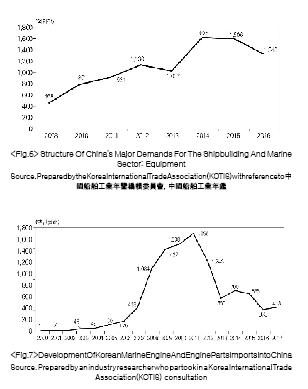

China’s shipbuilding and marine import market are formed by marine engines market and the core parts market. Of these, Korea is the largest market shareholder in the marine engine import market. China’s marine engine imports from Korea between 2008 – 2012 dropped significantly compared to the booming market from 2007 – 2008 which experienced large scale shipbuilding. Despite the slowdown, $300 million in imports was recorded. From 2010 – 2011, total marine engine imports amounted to approximately $2.6 billion, of which $1.4 billion (53.8%) came from Korea. Meanwhile, Germany has the highest market share for ship and marine parts imports. Korea ranks fourth after Japan and the United States.

3) Competition Structure Within China’s Domestic Market Between Foreign and Domestic Companies

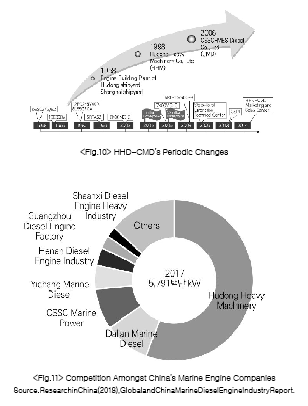

Competition between foreign and Chinese companies in the Chinese market is minimal in the ship and offshore plant market. Even in the case of equipment, most engines and parts are manufactured through joint ventures(JV) between foreign firms and SOEs, keeping competition to the minimum. Most notable firms are HHD-CMD, a JV between Mitsui Shipbuilding(Japan) and CSSC(SOE), Wartsila(Finland) and CSIC(SOE), and Mitsubishi Heavy Industry’s(Japan) JV, QMD(Qingdao Qiyao Wartsila Mhi Linshan Marine Diesel Company). QMD was a JV between Wartsila, Mitsubishi Heavy Industry, CSIC, and Qingdao Linshan Power Development; however, following a merger between Yichang Marine Diesel and Dalian Marine Diesel, QMD was renamed DMD.

(4) Shipbuilding Industry Policy Trends

The Chinese government’s policy on the shipbuilding and marine industry shows a strong commitment to supporting the industry in both the short-term and the mid-to-long term. Main targets of the national policies are marine, engineering, high-tech ships, marine exploration and resource development. China’s Medium- and Long- term Program for Science and Technology Development (2006), Science and Technology Roadmap to China 2050(2010), 12th and 13th Five-Year Plan(2011, 2015), Marine Engineering Equipment Manufacturing and Long-Term Development Plan(2011–2020), and Made in China 2025(2015) continues to be emphasized. Due to policy support, China far-exceeded its policy targets set for 2010. Also, in the case of offshore plants, China surpassed Singapore in the jack-up drilling market, which helped increase China’s marine support vessel market share.

Since the mid-2000s, during the global shipbuilding boom, China pushed ahead with the construction of large-scale complexes as well as aggressive investments by local governments and the private sector. As a result, the government actively pushed ahead with policy measures to mitigate the effects of economic downturns.

1) Support For The Exchange Of Old Ships For New Ships

This policy was announced in December 2013 by four government departments: the Ministry of Transportation, the Ministry of Finance, the National Development and Reform Commission, and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. This policy applied to all ships with Chinese registration. It aimed to change all old ships with new, environmentally-friendly and highly efficient ships by providing a subsidy of 1,500 Yuan per CGT to the ship’s owner. The ship had to be within 10 years of the mandatory dismantling age – owners received half the subsidy when the old ship was dismantled and the other half once the new ship was completed. If the mandatory dismantling age was 33 years, then all ships between 22 and 33 years of age were eligible for replacement support subsidies. Newly ordered ships had to be larger(CGT basis) than the dismantled ship. The support system was implemented until the end of 2015; however, was extended until the end of 2017.

Despite supporting the shipping industry, the policy was able to avoid WTO’s restrictions as it aimed to bring work to the shipbuilding and equipment industries, which are both downstream and manufacturing industries, respectively. The policy saw great success as over 40% of large capsize bulk carrier costs were covered by subsidies. Major Chinese shipping companies such as COSCO, China Shipping Development Co(CSDC) and China Shipping Group were among the beneficiaries.

2) Shipbuilding Industry Export Tax Refund

The Chinese government refunded export tax on products and refunded about 17% of the Value-added Tax on ships. In the case of domestically-used ships, similar incentives/benefits were offered to innovative ships or ships ordered by the government. The 17% tax refund allowed for 7% operating profit despite a deficit quote of 10%. This played a significant role in cost competitiveness and was a crucial factor to recoup competitiveness against competitor Korean shipyards. Unlike ships, ship blocks manufactured in China by Korean companies were no longer subject to the tax refund after it was abolished in 2007. As a result, the cost of hull blocks procured in China increased. The tax rate was recently been raised by 1 – 2%, further increasing Chinese government support.

In order to respond to the future market, smart, cutting-edge ships are designated as targets in the ‘Made in China 2025’ policy. The policy’s primary targets are providing solutions for the ship’s entire lifespan, data-based smart, cutting-edge ships, and intelligent equipment management and control functions. Recently, the state-owned shipbuilding group, CSSC, completed development of smart bulk carriers with government funding. And it appears that they have begun developing autonomous carriers.

The State Council selected 11 key areas – entrepreneurship, innovation, manufacturing, energy, finance, transportation, e-commerce, AI, the ecological environment, etc. – through the Internet Plus policy(2015) that can create models for new industries. Having done so, the government is in advocating the goals and specific plans for each area. These are all included in the ‘Made in China 2025’ policy and the 13th Five-Year Plan. Examining these in further detail, it can be established that marine engineering facilities and cutting-edge ships are continuously supported as target areas. The convergence of cutting-edge technology and attempts at reinforcing basic capabilities in the manufacturing industry with information technology, advances and ‘smartization’ of the manufacturing industry, and eco-friendliness are also applicable to the competitiveness of the shipbuilding industry. In particular, when looking at the periodically reinforced environmental standards set by the International Marine Organization, the Chinese government’s eco-friendly, ‘smartization’ plan will be the means to support the global market’s needs through its rapid and smooth response. Advances in the one-on-one policy of the Maritime Silk Road has many strategic links with the shipbuilding industry, so is expected to receive policy support.

※ Will continue next month.

- 이전글주요 산업의 중국 지역별 특성분석과 시사점(조선) ① 19.10.30

- 다음글Review Of The Korean Shipbuilding Industry’s Ideal Production Capacity 19.10.30